CONTENT WARNING: This essay contains drawn depictions of sexual assault amongst other uncomfortable subject matter.

.

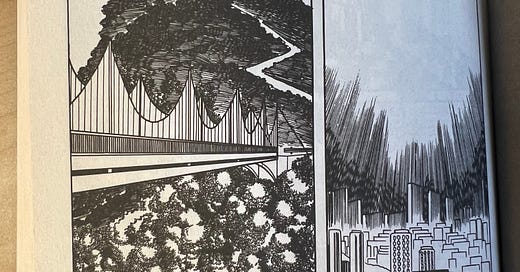

Osamu Tezuka made some weird, stupid bullshit in his life. To my surprise, that tends to be the work in his catalogue I respond to the most strongly. RECORD OF THE GLASS CASTLE has lingered in my mind since I first read it last summer, either despite of or because of its seemingly unfinished quality, its oddness of narrative prioritization, its uncomfortable depictions of greedy men and helpless young women that echo forward into more complete works like AYAKO.

GLASS CASTLE was the first of the Tezuka translations I read by DMP Platinum Manga, a company doing the Lord’s work for completionist weirdos like me by translating into English some of Tezuka’s Japanese only manga works. The synopsis, from DMP itself, reads:

“In the Glass Mansion, a family has been frozen in cryosleep for 20 years under the orders of their patriarch. When the oldest son Ichirou awakes, he struggles to accept the reality that he has slept away 20 years of his life. Ichirou plans to exact revenge on those in his family that stole his life from him. As Shirou, the youngest brother, attempts to stop Ichirou, he becomes aware of the dangerous side effect of cryosleep that led to its national ban years ago. How far will Ichirou fall, and will Shirou be able to stop him?

In Record of the Glass Castle, Osamu Tezuka tackles the great quandary of immortality at the cost of humanity, in a different, much darker light than he often does in his better-known masterpieces like Phoenix. In this tale, the search for humanity seems more hopeless than ever, tangled in hatred, greed, and lust. This one volume series is a must-read for the fans of Tezuka’s dark side, as well as those who can appreciate a story that won’t spell out all the answers.”

That pretty well describes what happens in these pages. What it does not represent is that this book is dribbling apeshit bonkers, punctuated by extended passages that are cryptic, gesturing at thematic intent while simultaneously being boring and sometimes flatly confusing. It may not sound like it, but I really love this book.

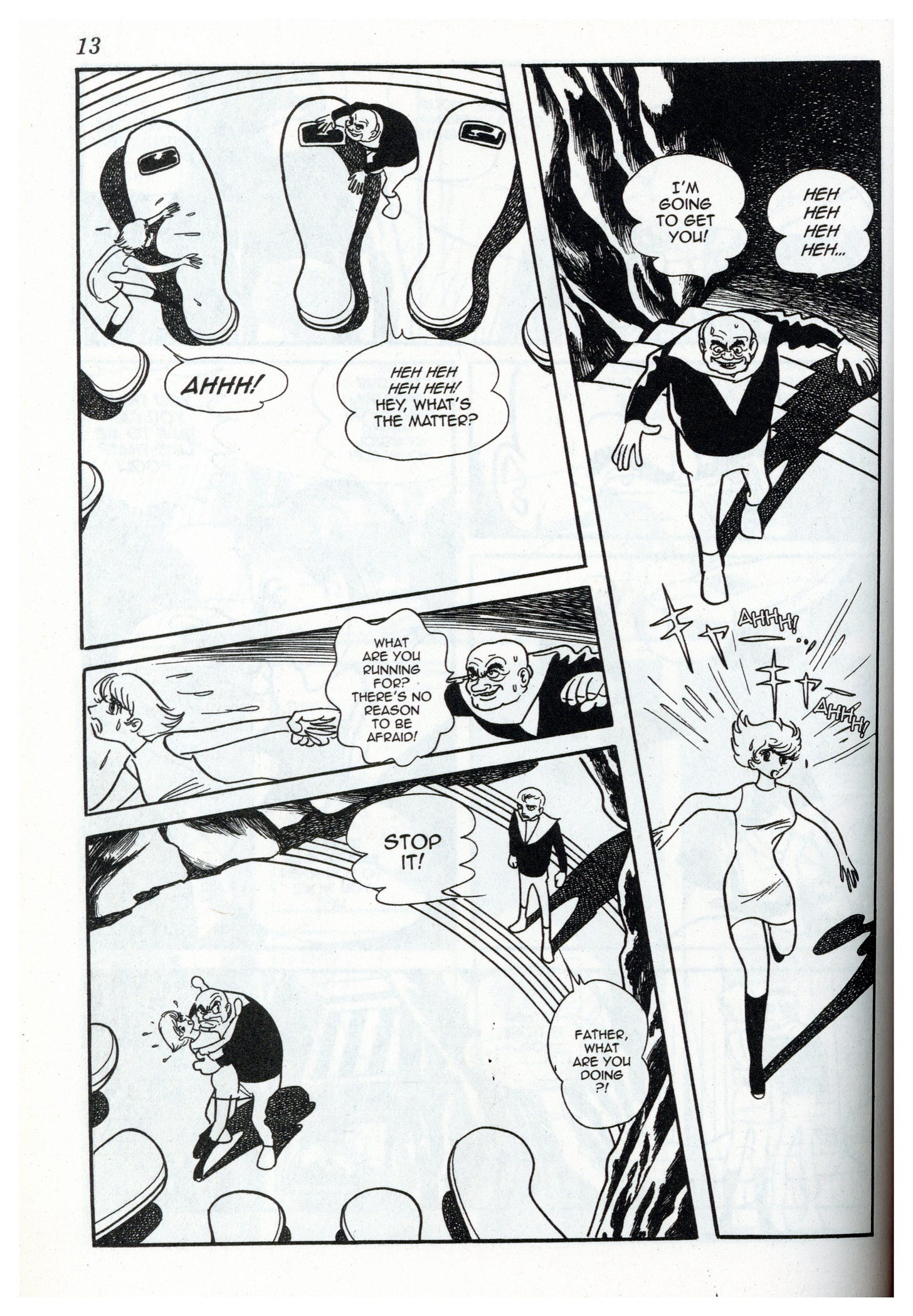

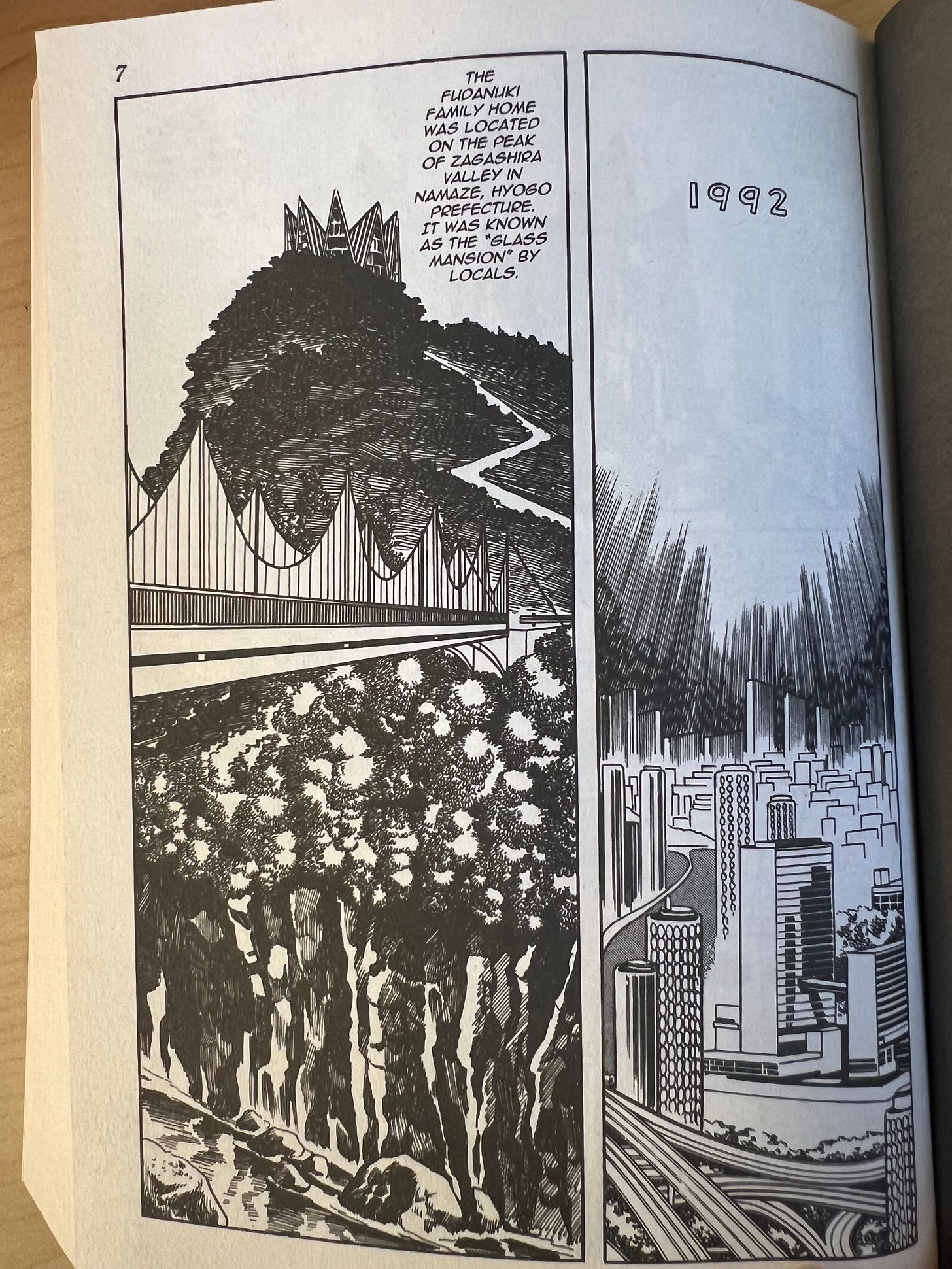

The titular Glass Castle is the home of the wealthy Fudanuki family, most of whom are preserved in suspended cryogenic youth. The first Fudanuki we meet is the familial patriarch, Reikou, a balding captain of industry type described as “A boar of a man who did not even try to hide the terrible things he had done.” He’s seen by the help once a year. Naturally, this is because he’s only defrosted once a year and wanders his property in a lecherous, maddened haze.

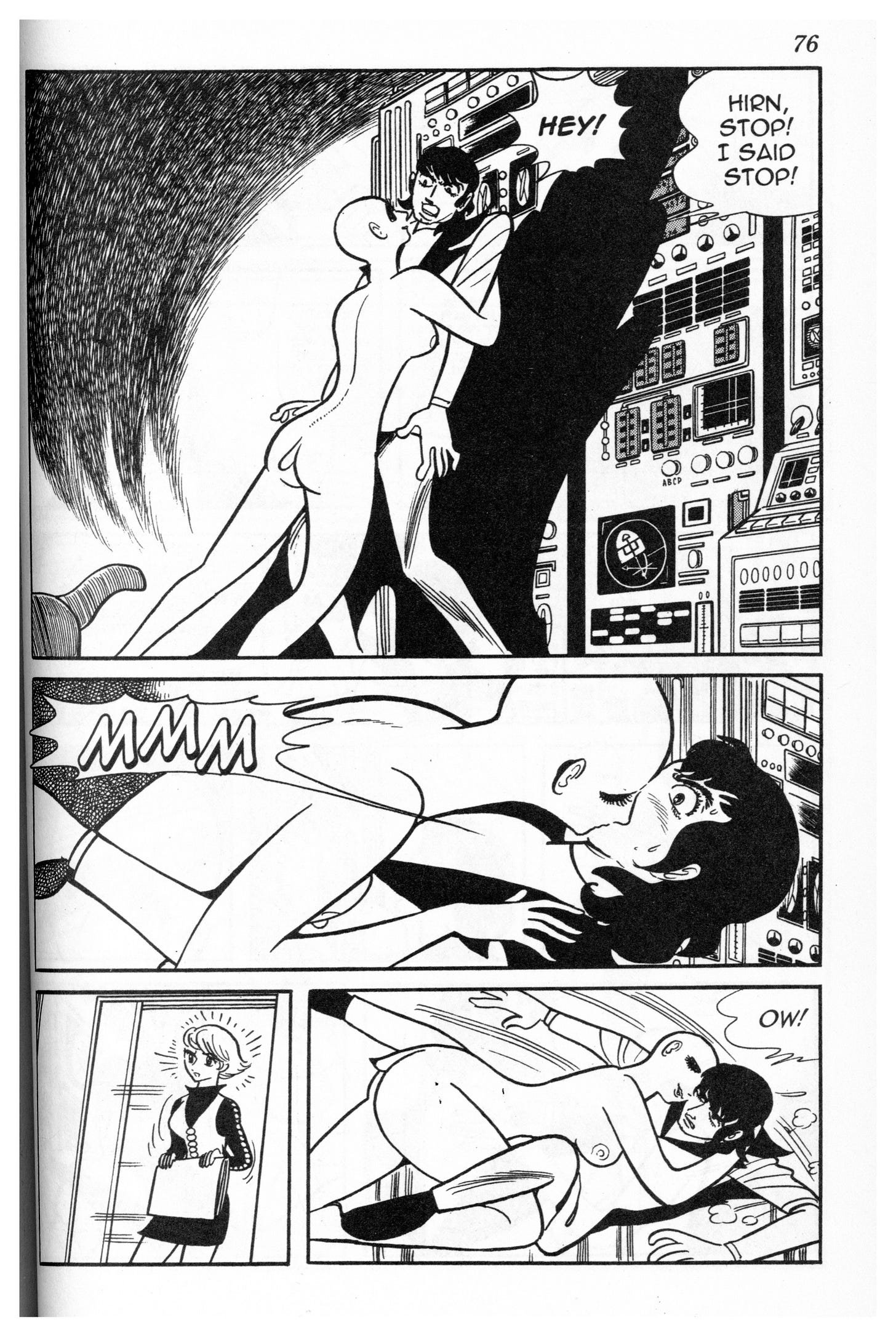

A lovely understated sequence of Reikou entering the cavernous hall where his frozen family is stored leads directly to the introduction of Mari, Reikou’s shy, meek and respectful granddaughter. Her age is not explicitly stated, but having been born within the twenty years her extended family has been frozen, we can assume late teens. Reikou makes a bestial and immediate attempt at sexual assault on his granddaughter before he’s halted by Shirou, his second-oldest son. Shirou is the caretaker of the family cryo-pods, and has aged normally over the last twenty years.

Shirou is an interesting character right off the bat. He bemoans being a natural forty-two years old, while his family has remained in stasis. He both disdains and envies the family members who were frozen, hanging onto their youth unnaturally while he shows signs of age, harboring two decades of contempt. He is also immediately moral enough to stand in the way of his addled father’s animalistic lusts and comfort his daughter once Reikou is redirected elsewhere.

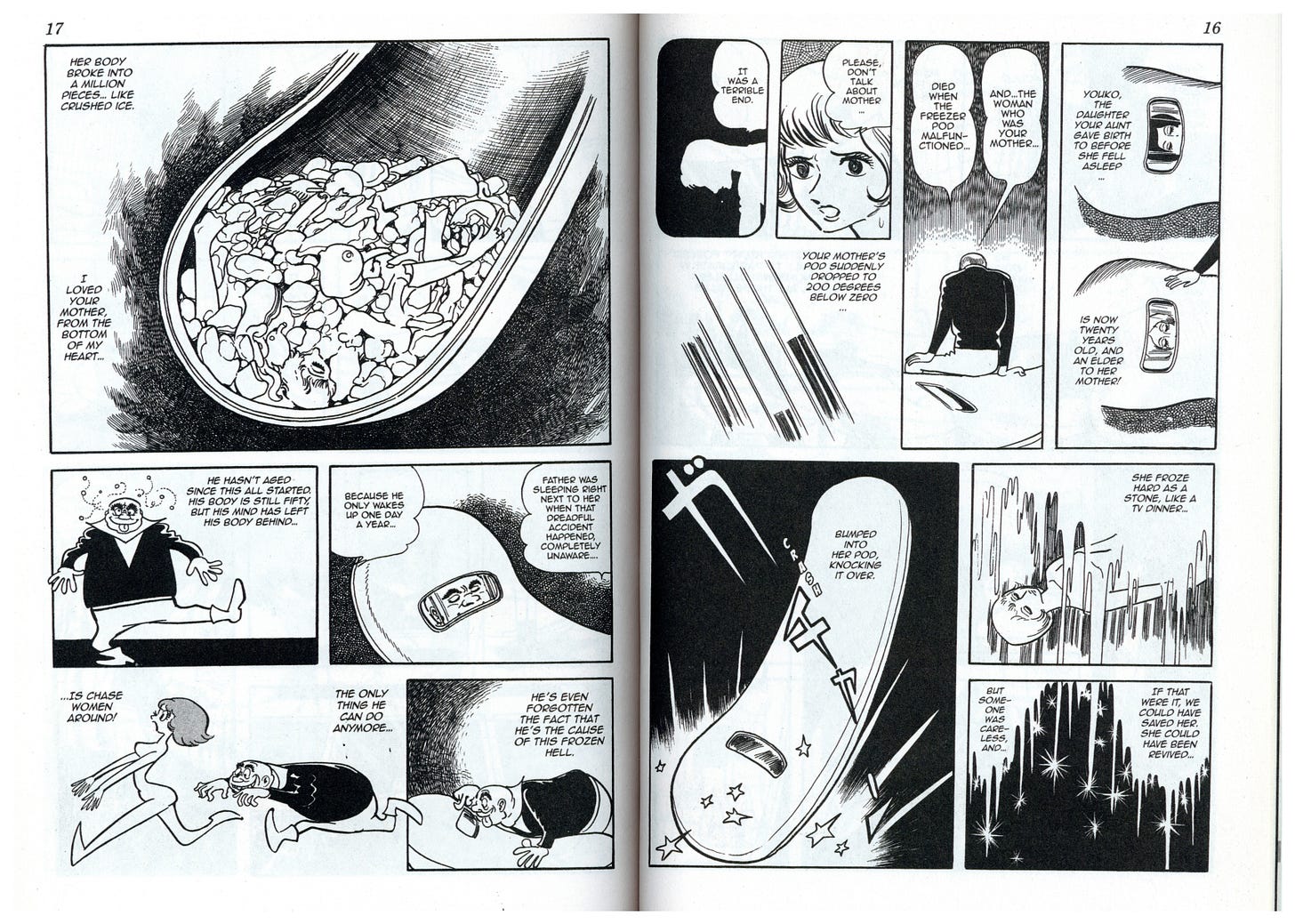

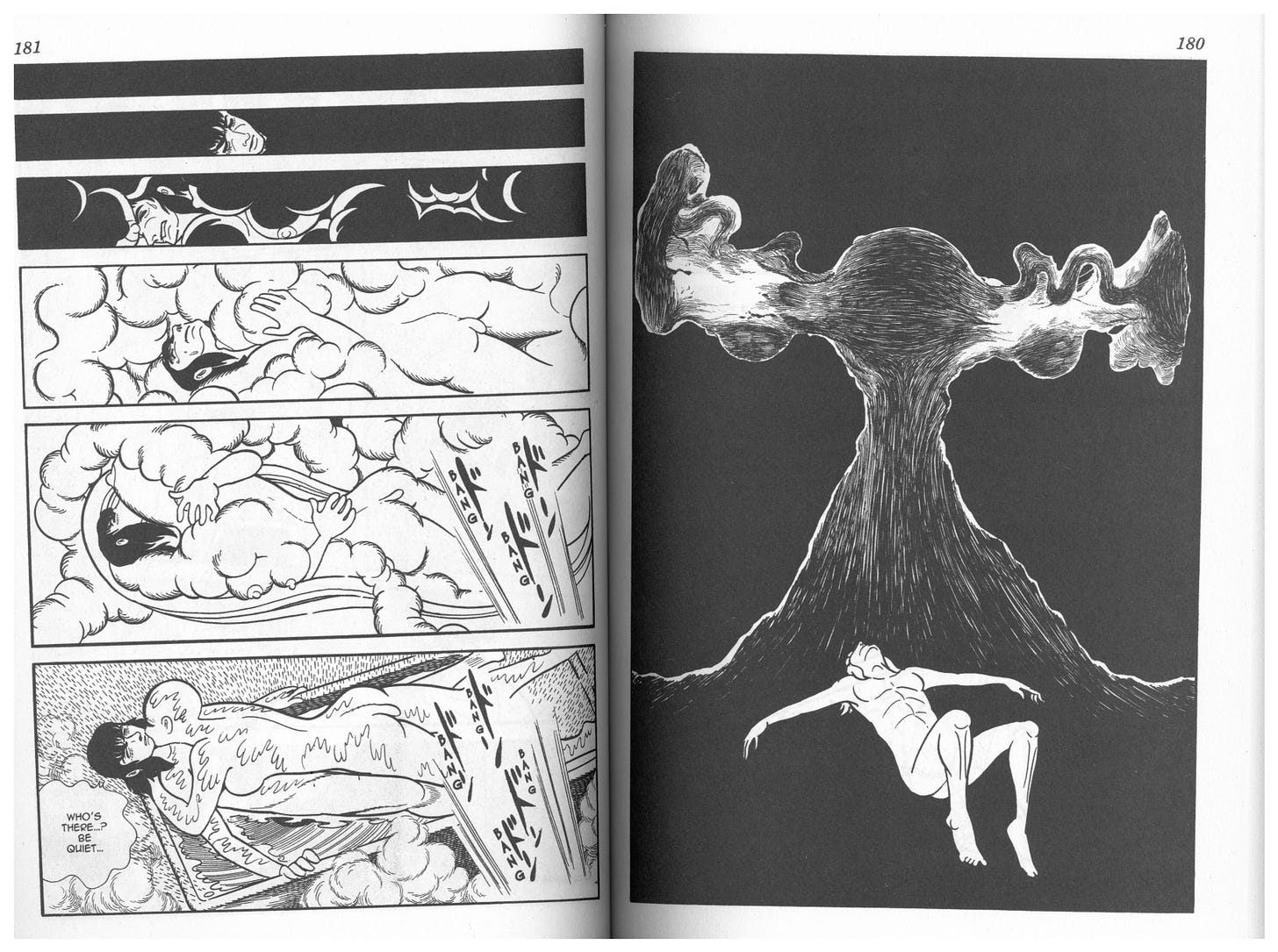

Guiding Mari and the reader around the pods, he introduces Mari’s older brother, frozen forever at two years old, still a baby after twenty two years of life. Shirou’s sister, frozen at eighteen, beside her own daughter who was frozen much later and is now physically older than her own mother. Tezuka presents a particularly horrifying and beautiful sequence describing the fate of Shirou’s wife and Mari’s mother, whose cryopod dropped to an unsustainable level of cold. Her pod was carelessly bumped and its contents, Shirou’s wife, shattered like glass. Tezuka flexes a largely unseen muscle here, an ability to construct a scene of sci-fi body horror, juxtaposed with the understanding that Reikou’s mind has broken during his time on ice. He has lost himself, only his lusts and ego remaining, incapable of remembering even that he was the one who gifted and condemned his family to this fate.

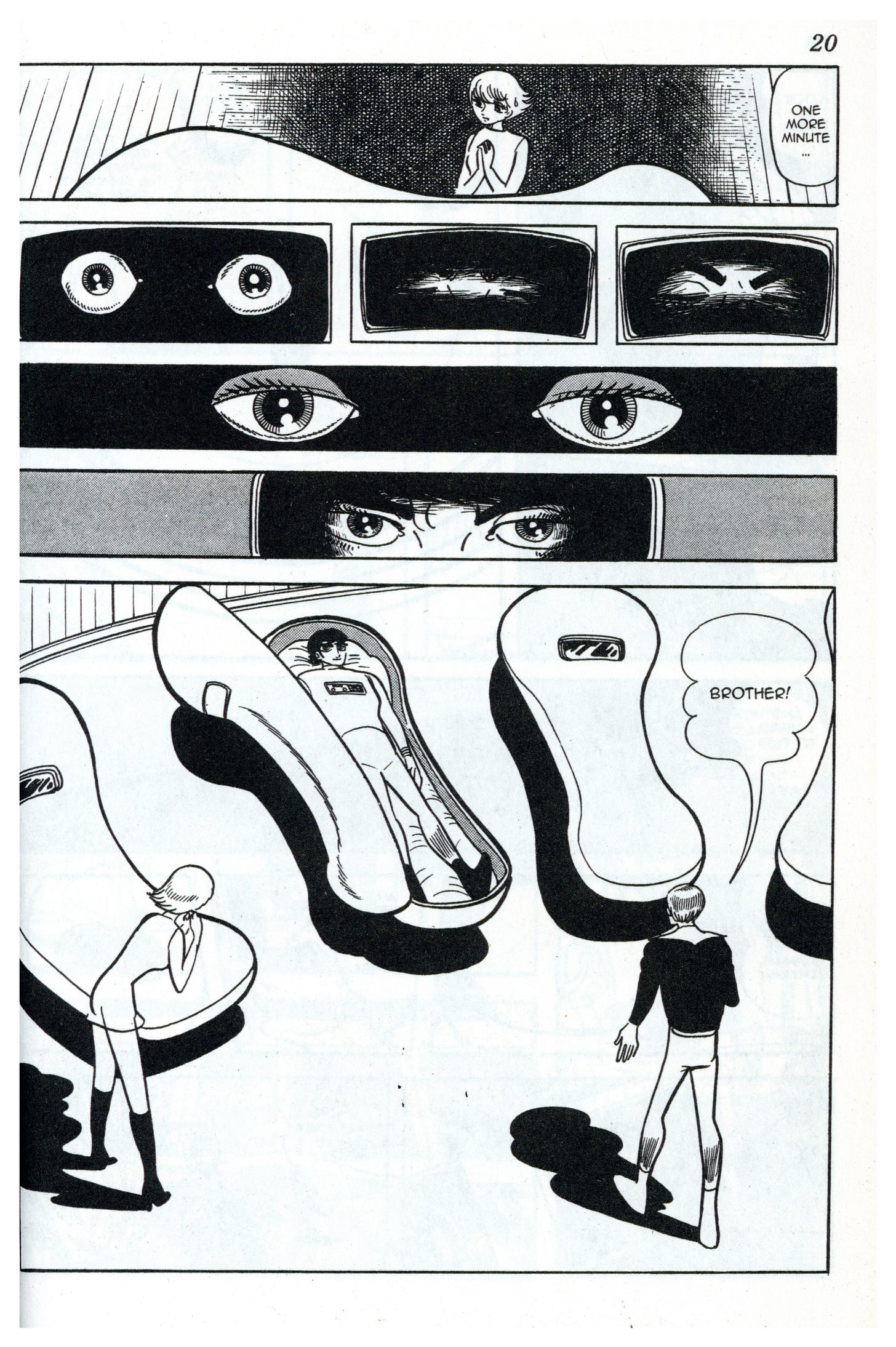

So far, what an opening. The characters are distinctly drawn, both as lines on the page and in terms of narrative characterization. Themes of regret, the physical and psychological costs of immortality, a relatable skepticism and mistrust of the super-rich and the nigh-magical technologies they hoard for themselves. It is at this point that Tezuka introduces his principle character, the messiest element of the story and its primary driver from here on out, Shirou’s brother Ichirou.

Shirou has grown tired of being of stewarding his family’s frozen well being. He wants a taste of it himself. At forty two, he fears the best years of his life are already behind him, and wishes to awake again in a future where he’s still youthful enough to make the most of a more advanced world. This requires someone else to take over, and Shirou decides that Ichirou has had enough time on ice and it’s his turn to keep an eye on heartbeats and defrost dad once a year.

At this point, I want to step away from summary and examine some of the broad-strokes thematic work Tezuka is doing on these pages. The decline in Reikou’s cognitive abilities is presented initially as the sad but predictable senility that comes with age. It’s hinted at, early on, and later confirmed, that the cryo-sleep claws away at wellness of mind and reason, grinding those who undergo the procedure to a kind of narcissistic madness. Shirou and Ichirou have nothing but contempt for their diminished robber baron of a father, though we see that this anger comes from different angles. Shirou feels left behind by the future, abandoned to toil pointlessly in the present as age claws crows feet around his eyes and ache into his bones.

Ichirou’s anger comes from a reasonable place. In a flashback, he demands to know why he should have to be frozen at all. His father explains straightforwardly: they already have vast wealth. Said wealth accrues interest. When they awaken in the future, they will be even richer than they are now. And, like, that’s it. Given that as i write this, a small handful of centibillionaires are influencing the office of the United States presidency more than any of his senate-confirmed appointees, this proletariat distaste for the indulgences of the super-rich rings perfectly true to me.

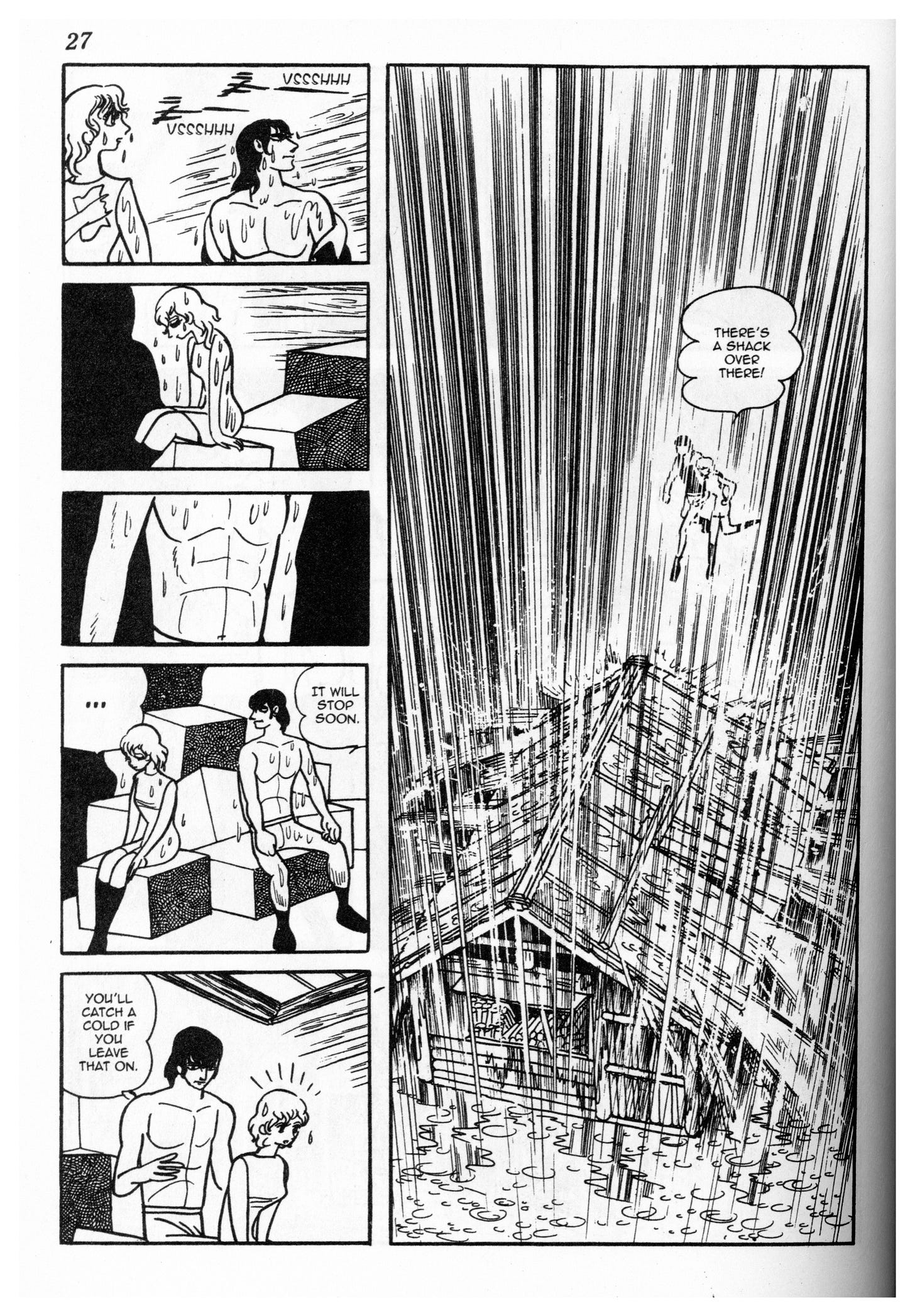

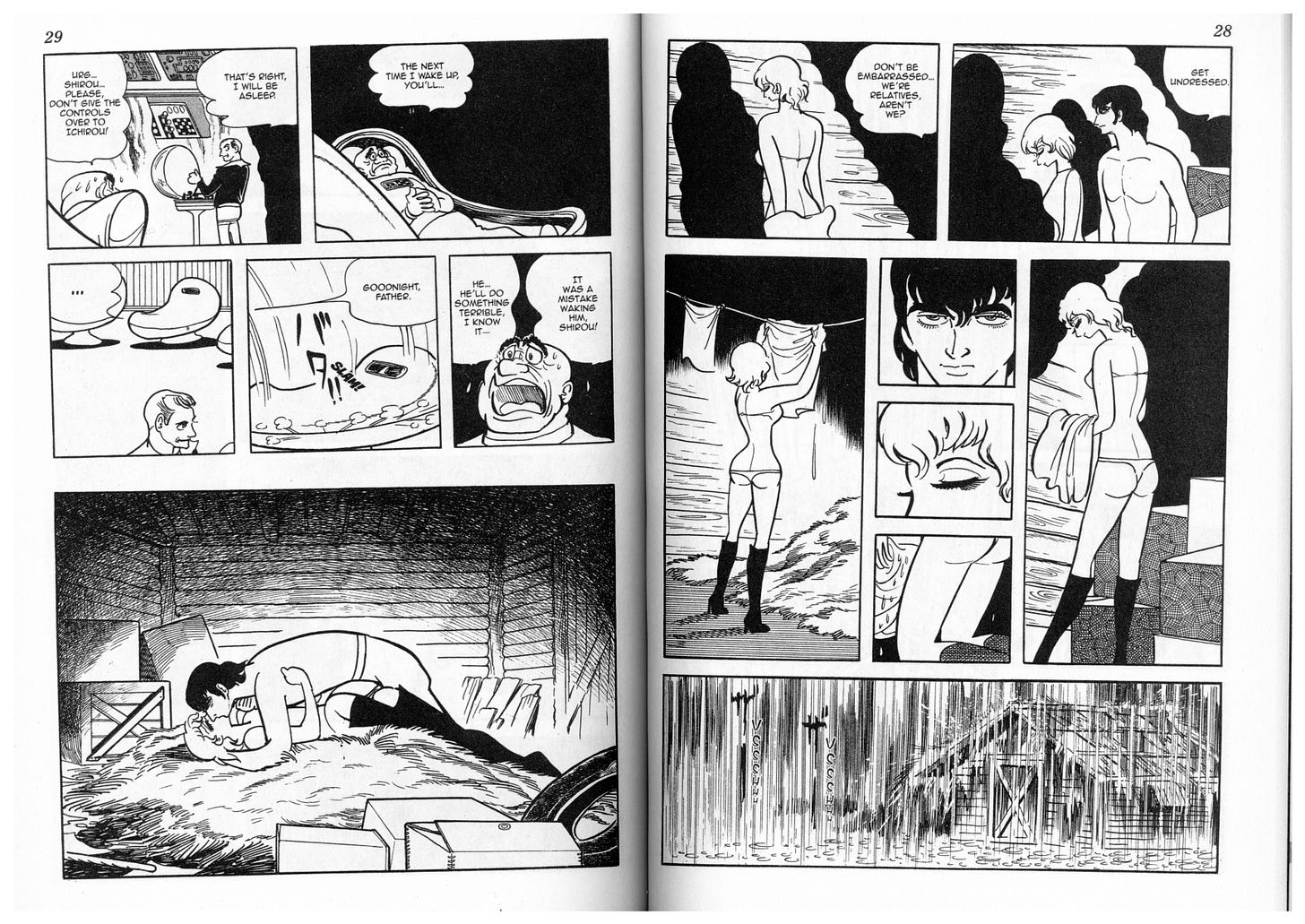

In the context of this story, of course, Ichirou is just as rich and entitled as his father. He has different priorities and values the notion of an unearned future skeptically, but this view comes from another broken mind that values human life not at all. It seems to me that Tezuka is demonstrating the ways in which unaccountable wealth deforms one’s morality, a point I consider more or less inarguable here in 2025. Ichirou is presented as being at odds with his father, but we see shortly after his introduction that he is truly no better. Out on the Fudanuki property, in a shack beneath a sudden rainstorm, Ichirou rapes his niece.

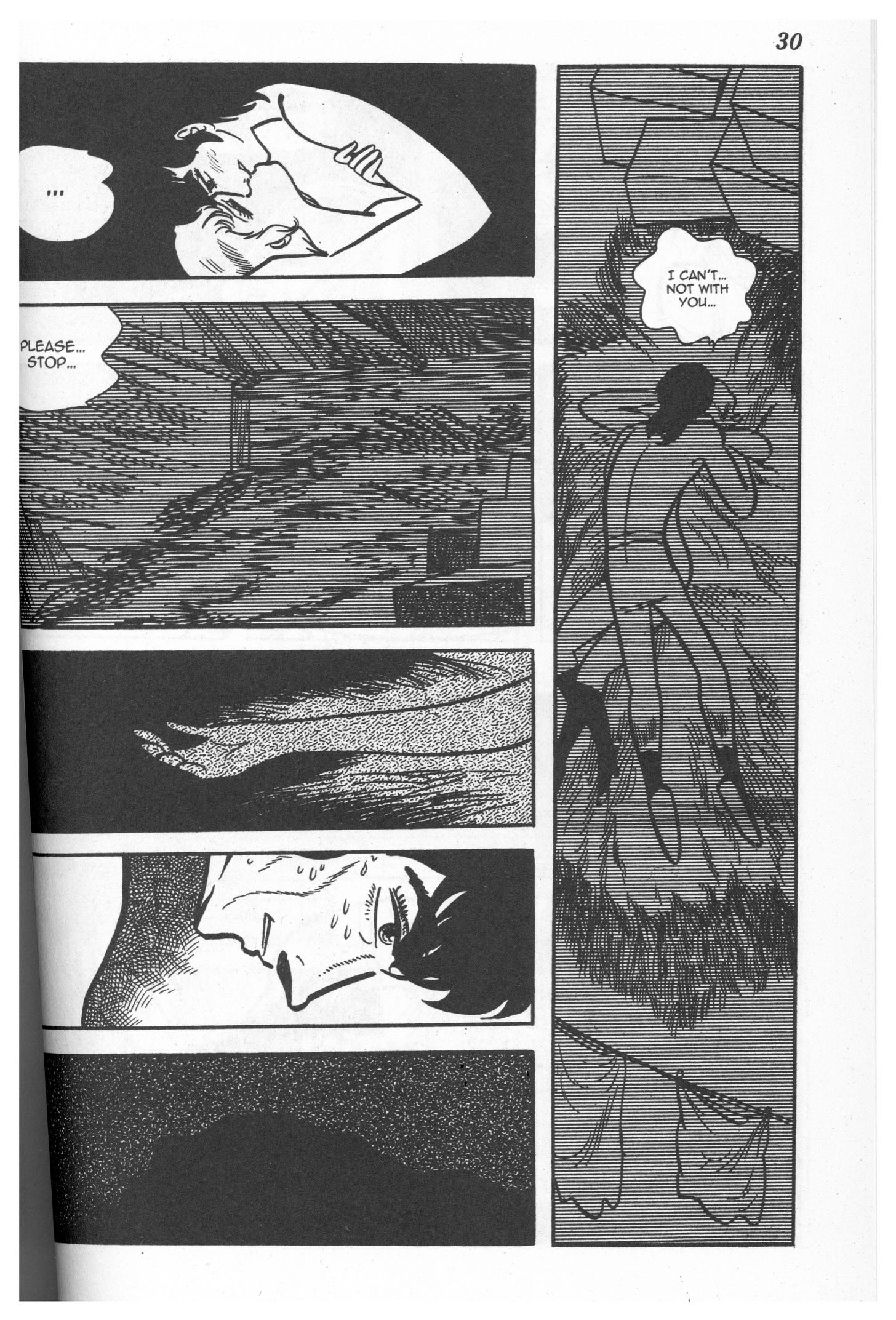

I do not include this sequence as an attempt to titilate. It is presented as unambiguously awful and intentionally disturbing, and it does not read to me as a juvenile attempt at shock. Tezuka made a deliberate artistic choice to lay out, pencil and ink this multi-page scene to demonstrate to his readers that Ichirou is a selfish and manipulative predator, to whom even the taboo of incest ranks far, far beneath meeting his immediate desires. As a reader, it is wildly unpleasant at the absolute minimum, and it occurs within the first thirty five pages of the story. Ichirou is quickly rendered plain and unambiguous. He is the villain of GLASS CASTLE, and from this point on, he is also our primary POV character.

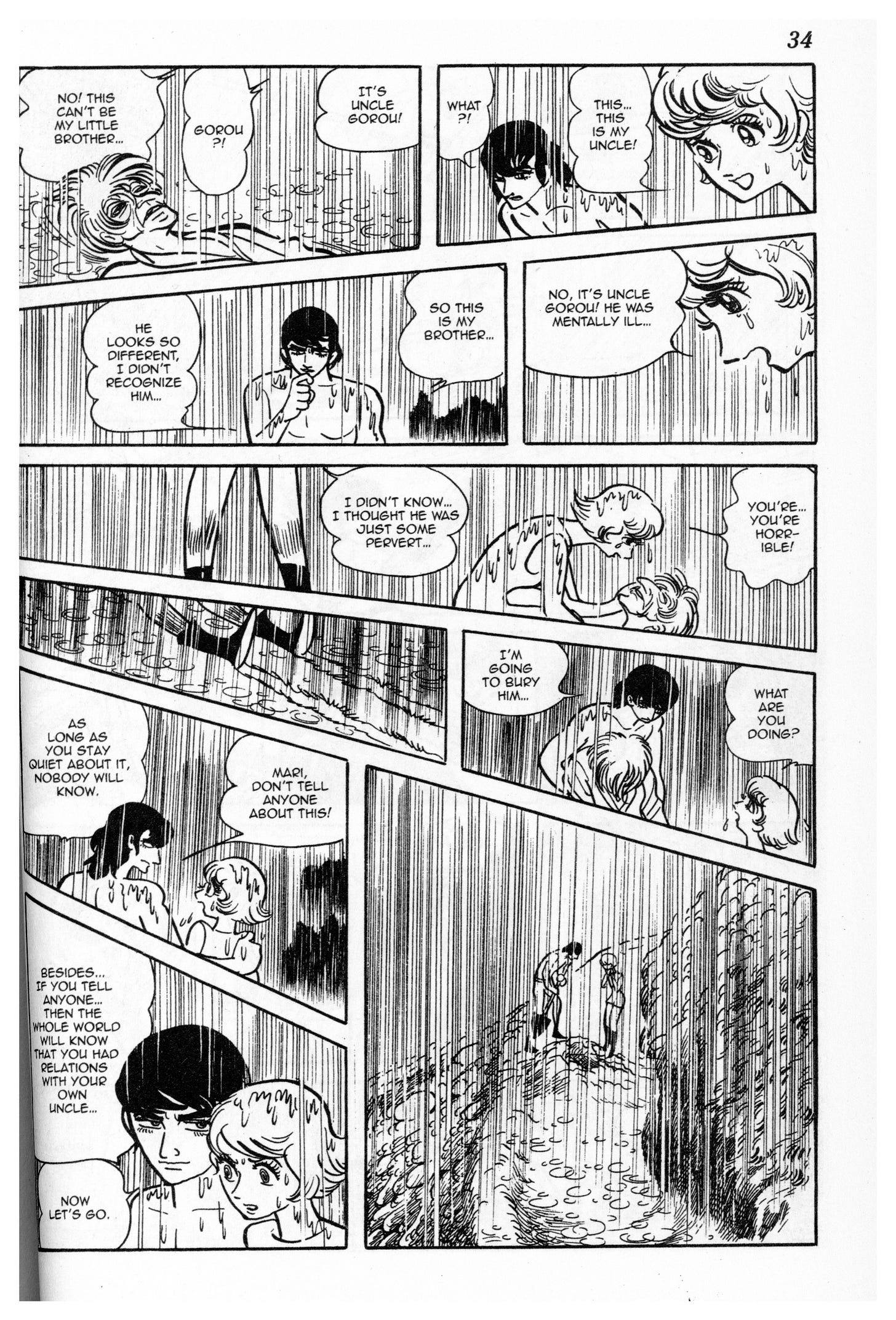

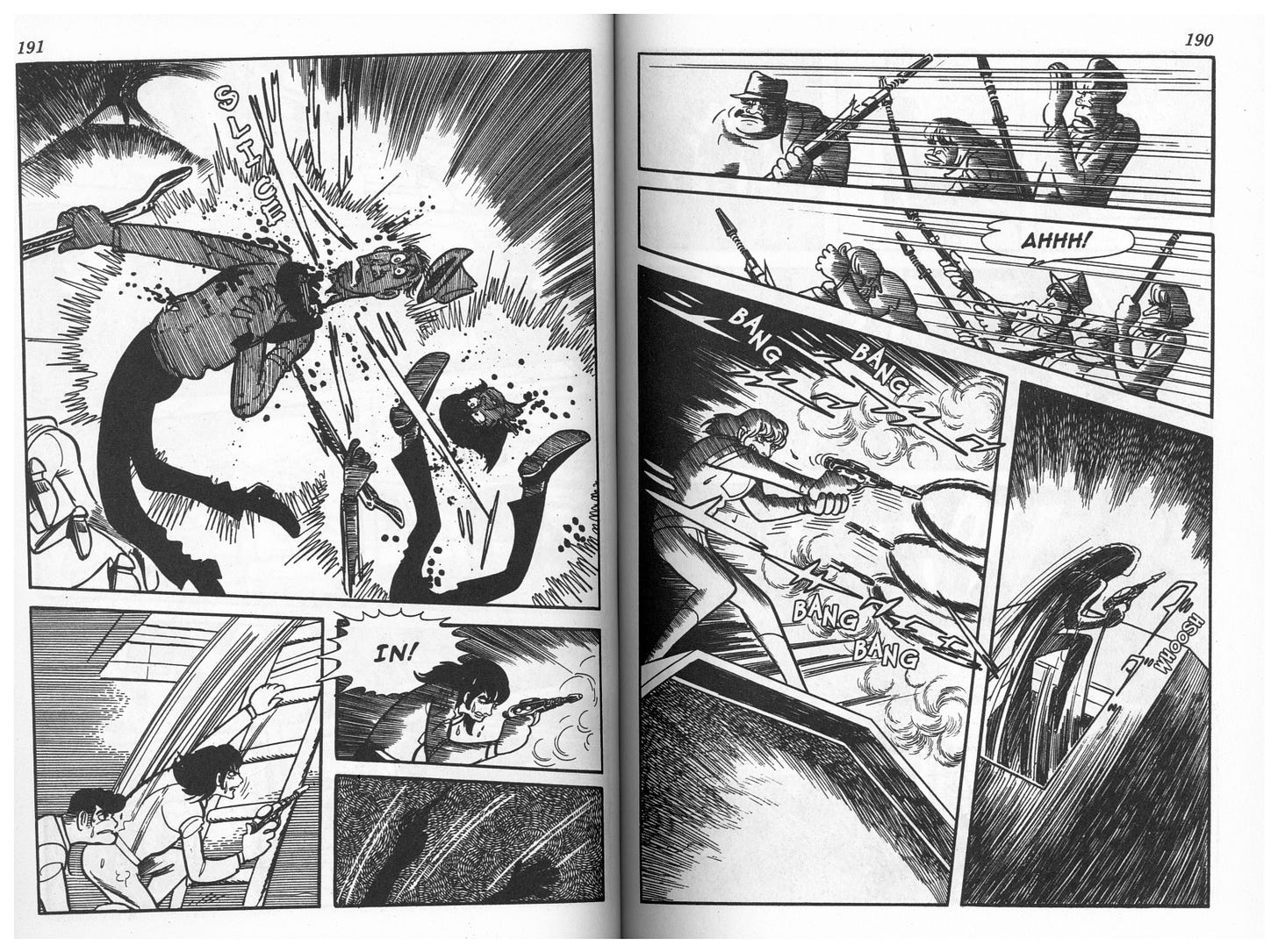

In case anyone missed the massive red flag fluttering around Ichirou, he moves from rape to murder in only two pages, killing a mysterious figure who had been watching his foul act. This figure is revealed to be his mentally disabled brother Gorou, slain by pitchfork and bludgeon, and extortion is added to the list of Ichirou’s iniquities. Osamu Tezuka tends to render his narrative and emotional beats in all capital letters in his gekiga work, and he is stating as plainly as he can that Ichirou fucking sucks.

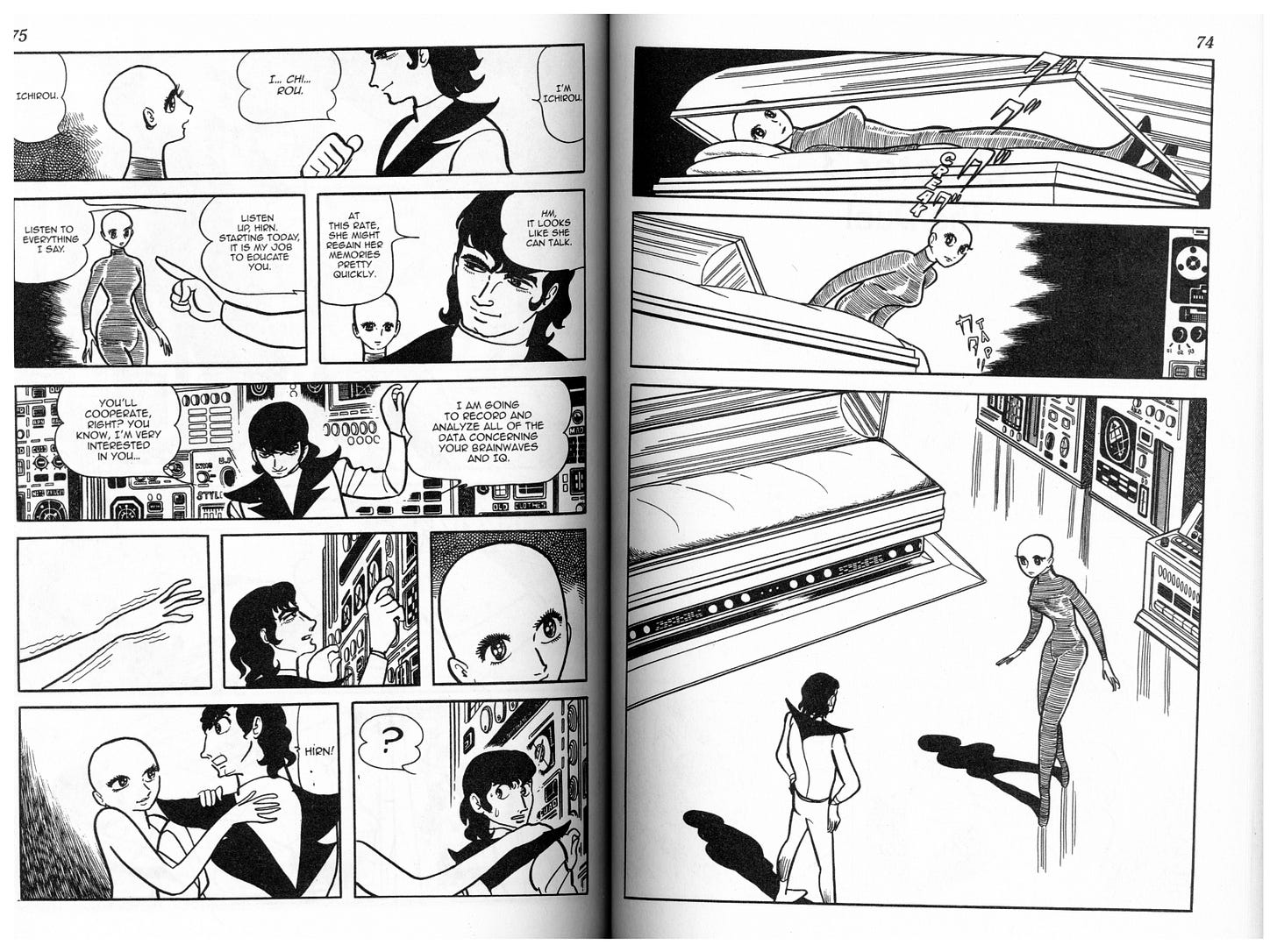

All of this occurs within the first forty pages. The artwork is so different from his work on books like Astro Boy or even Buddha. There is so much black on the page now, dense and claustrophobic. Tezuka famously had entire inking guides to be handed to his assistants after he laid out pages and inked the primary characters and compositional elements. He was not interested in bringing in artists with their own artistic impulses to collaborate on his work. He wanted artists who could visually communicate the Tezuka style, and nothing else. This is clearly the same hand, or assembly line of hands, that built Buddha, but turned to such distinctly different creative priorities. Rendering in a reduced, legible manner that is, for example, sinister or threatening is one of those odd and difficult to describe pieces of being a cartoonist. Tezuka possessed more than enough mastery of his craft to guide a bullpen of (I can only assume) chain-smoking, sleep deprived young trade school artists, bending them to his will and vision.

In one of the greatest comics ever created, Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s A DRIFTING LIFE, Tezuka himself is featured prominently as guide and god to a young generation of manga-ka attempting to find their place in the artistic space manga occupied in Japan in the mid-twentieth century. This book (which is being reprinted by D&Q soon, and I cannot recommend highly enough) deals directly with the historical creation of gekiga, manga for adults, of which Tatsumi is a Moses-like figure. Laying the path through the wilderness behind him, that other magnificent artists might follow with work meant to be more challenging and dense than what had come before. He was hardly alone in this endeavour; personal favorites like Yoshiharu Tsuge and Shigeru Mizuki blazed their own parallel trails through the kid stuff that dominated the industry at the time.

Tezuka was competitive. He was not content to be the king of kid shit; he began producing gekiga of his own, of which GLASS CASTLE is an aggressive example. You want stories for adults? Have it. Have as much as your tender muscles can bear.

Tezuka’s adult work is fascinating to me, both for how natural the creative pivot seems in hindsight, and for being so of a piece with his earlier all-ages work. Returning to CASTLE, however, we begin to see the frayed edges of the thing, and much of the excellent early storytelling being done in this book starts to fall apart. Themes deprioritized, characters slotted in and forgotten, sci-fi elements introduced and glanced at momentarily, replaced with the narrative threads of a secret agent thriller. I reiterate, as forcefully as the written word can allow: This is VERY strange book.

Ichirou roasts his father alive in the cryo-pod where he slumbers. He kidnaps Mari, forcing her to drive a car away from the mansion, further reiterating the control he has over her as they make their way into the city to meet with an unsavory connection of Ichirou’s before he was frozen.

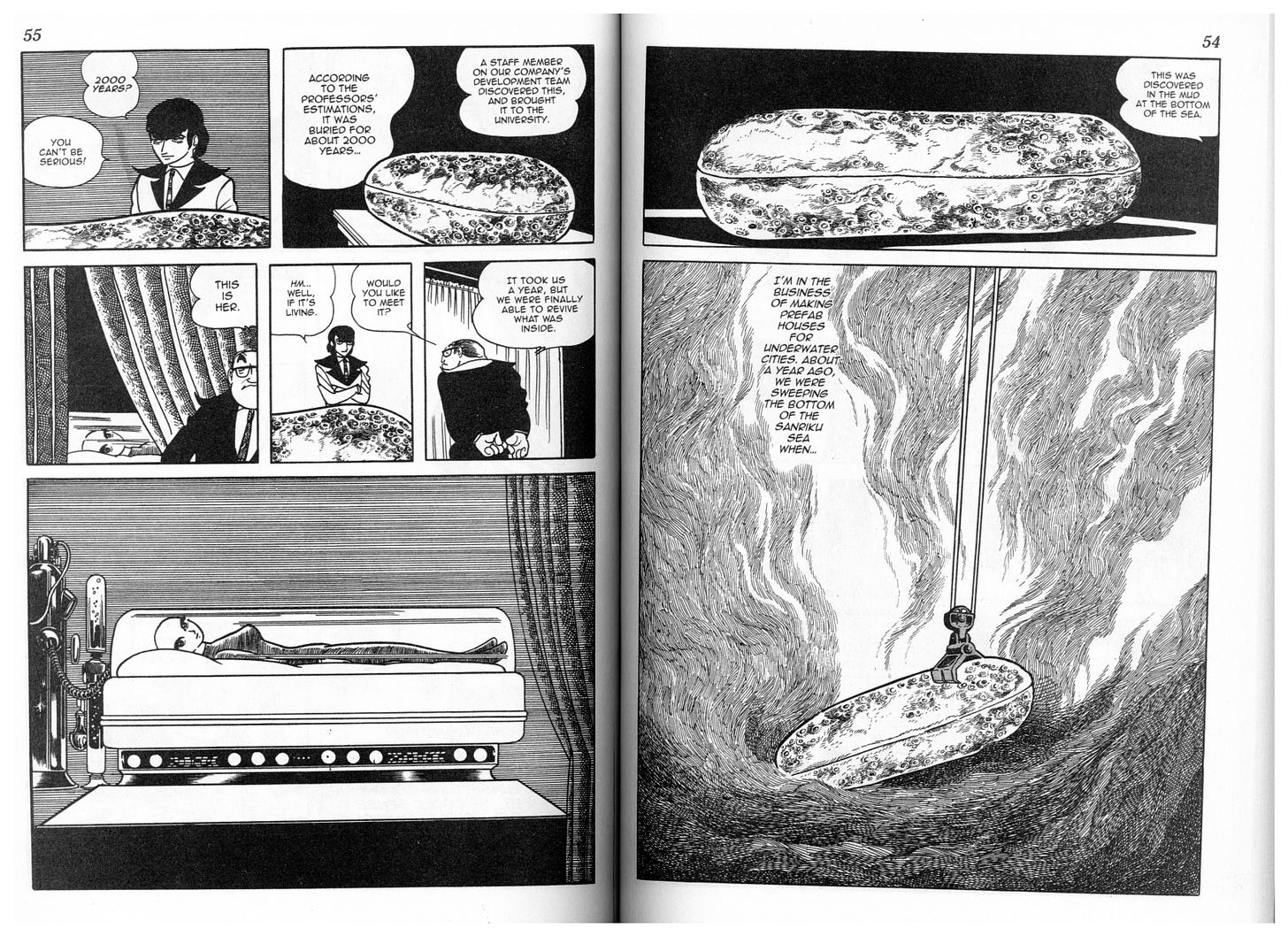

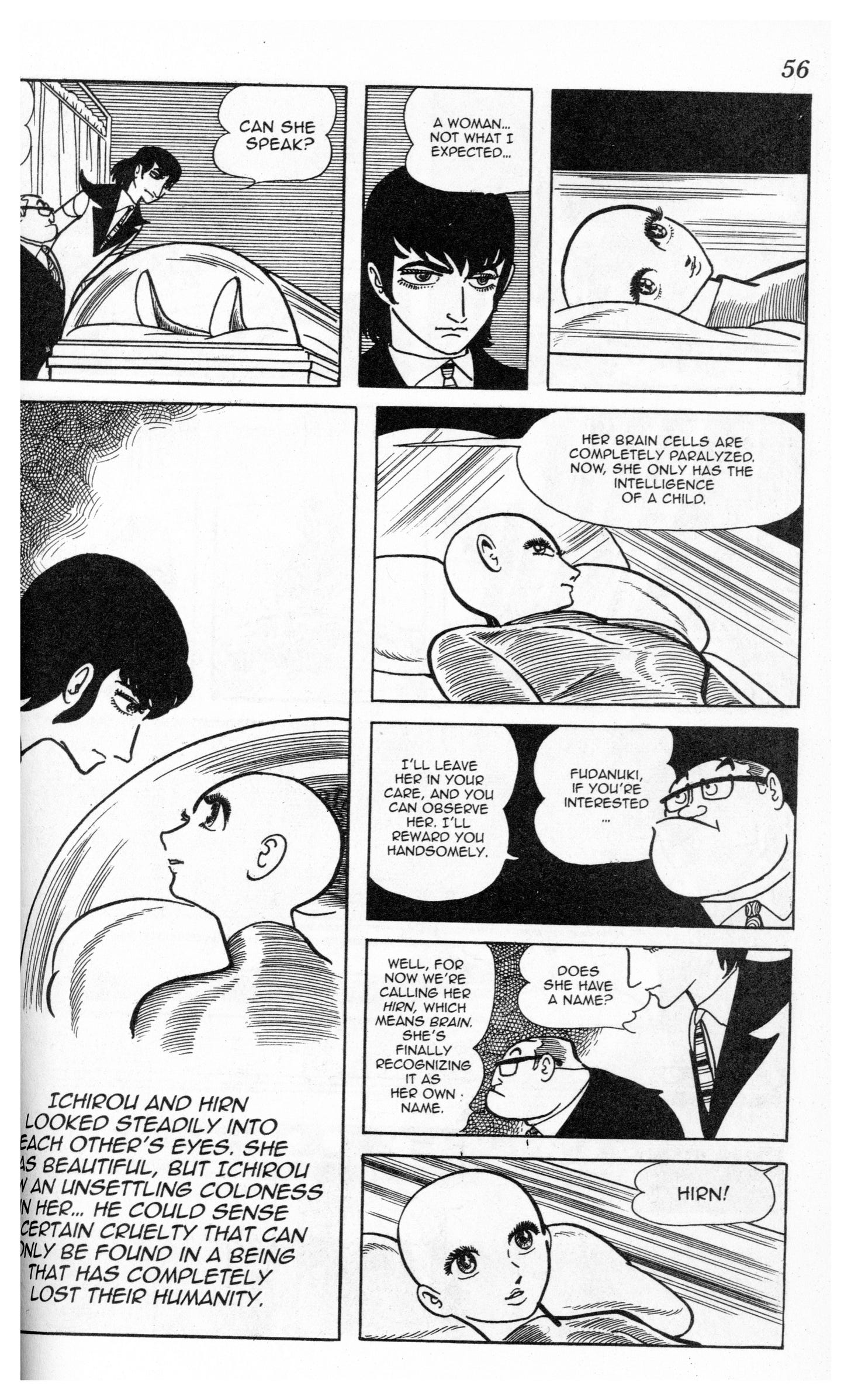

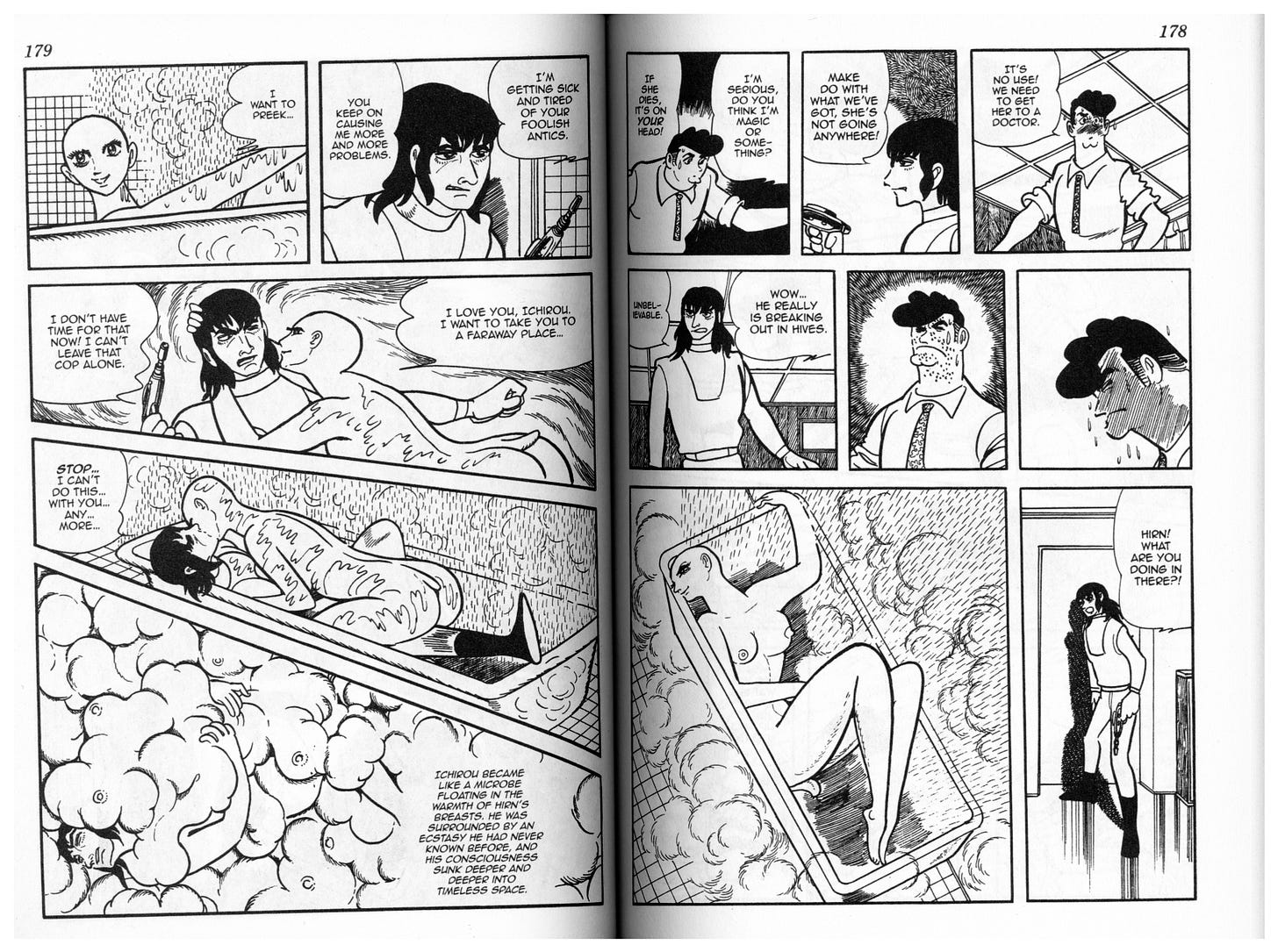

This connection has an odd piece of narrative and thematic fabric: A young woman, frozen for two millenia, buried in a sarcophagus beneath the sea. This character, Hirn, is the seeming dry run for AYAKO, a young woman denied experience of the outside world and left to be molded in the hands of the men who define the shape of her prison.

Hirn is placed in Ichirou’s care as Mari sneaks home to see what’s become of her family. Shirou and co. are awakened, learn their father has been functionally melted in his coffin and that Gorou has been killed, and for added fun, Mari confesses to Shirou that she is in love with Ichirou. These parallel sequences of Hirn’s introduction and Mari’s return home represent a murky and unwelcoming corner of Tezuka’s tremendous artistic range; The diminishment and simplification of women in GLASS CASTLE.

I have difficulty determining the value of holding a book like GLASS CASTLE to modern standards of ethics and taste. Tezuka has been dead for thirty five years. I will never meet him. He was born more than a half century before I was, into a culture that I am simply not part of. I don’t pretend to understand what Japanese cultural attitudes were towards gender in the seventies even superficially, much less Tezuka’s specifically. With all of that stated plainly, Hirn and Mari are both presented distastefully by any contemporary standards.

Mari is flatly a victim throughout the course of the book. She is preyed upon by her uncle, flees her captor to confess to her family that she loves him, returns, and is further brutalized before the end of the story. Some people do, in the real world, return to their abusers. There is nothing to condemn or blame in the victim for this behavior. It’s one of many possible advancements along the cycle of abuse that some people cannot escape. They deserve sympathy, understanding and patience in the real world. Tezuka offers none of that to Mari in the framing.

As a writer of fiction, I have bitten off more than I can chew. I have begun excitedly writing about topics or themes that I am certain I understand well enough to do justice, and more times than I can count, I’ve run into the brick wall of my own limited capacity. Other creative priorities take up more space. The story contracts around something I thought I understood, smothering it. Entire storylines and characters have slipped wordlessly away within finished stories, the unfinished and misunderstood wreckage an uncurated distraction on what I had hoped would be cohesive and whole. If I’m being very generous, one writer to another, that could be what happened with Mari.

OR it could be that Tezuka finished this book in a short matter of months like he always did and gave little thought to Mari outside of her utility to Ichirou’s story. Mari is sheltered and innocent, violated by her uncle, utterly devoted to him and, honestly, barely a character. She has almost no agency in the story. She’s always either being captured or rescued. She goes where she’s told to go, does what she’s told to do, and when she does choose to do something independently, it’s almost always to return to Ichirou’s side. This is a sad character arc, but the pacing doesn’t give the bleakness of her situation time to breathe. There is an interesting story in everything under the sun, and so much of that story is in presentational framing choices, everything from how a character reacts in a given situation to the language (verbal or visual) used in context. Mari gets almost none of that. What she does get is repeatedly physically abused.

Hirn is by far more active in the story, though everything she is or wants is defined by Ichirou. Speaking of irresponsible speculation, I don’t particularly enjoy it when people presume to know the kinks and sexual desires of an artist. The counterargument in this case would probably go something like, “well, just look at it.”

Hirn is irrepressibly lusty, a primeval holdover from a more sexually free time when people had tails, and utterly devoted to Ichirou. Taken in the greater context of Tezuka’s work, she’s a spiritual sibling to Ayako, another woman who lived most of her life shut away from society, her edenic innocence preserved and tested by the world into which she’s freed. I don’t know what Tezuka’s thing was, and I don’t really care, but honestly, doing it twice, it’s hard not to see that maybe dude was kind of into it.

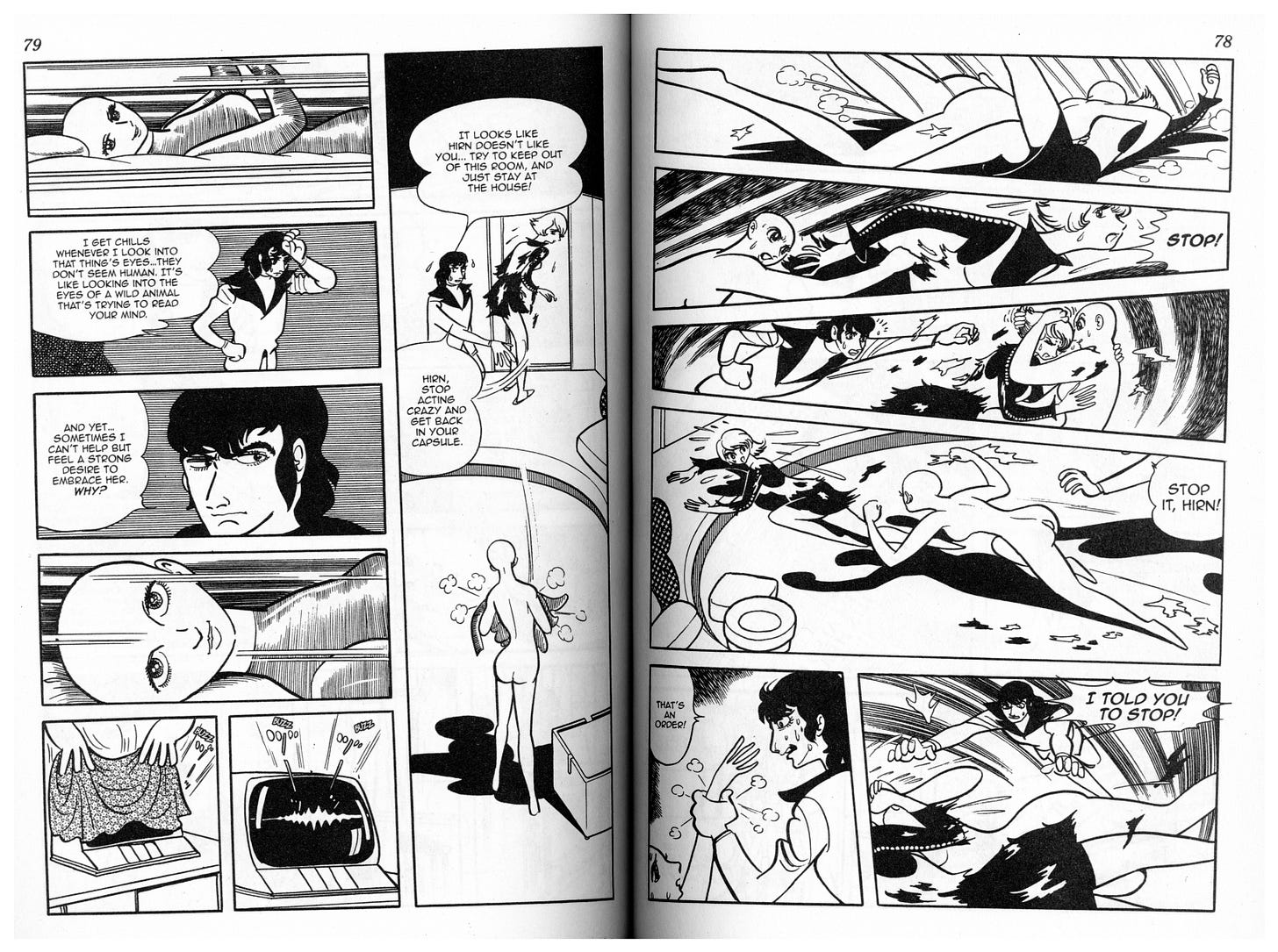

Hirn is immediately violent towards Mari, attempting to kill her rather than share Ichirou’s attentions with her. Later, she encloses Mari in her longtime tomb, disguising herself with a wig to appear more like Mari to Ichirou. Later still, She stabs Mari, perhaps to death. She appears to be in the story as a kind of secondary or parallel image of Ichirou; frozen for years, out of place in this world where she finds herself, unconcerned about using her body for whatever the situation calls for. She has no care for human life outside of her chosen beloved, and leaves a bloody trail behind her. She and Ichirou were made for each other.

The problem with Hirn is not the violence or the sex, it’s that she exists in the story only to make our hero Ichirou feel more powerful and awesome. She has greater characterization than Mari, certainly, but faint praise. She has no desire outside of Ichirou. This is not presented in the story as a mirror held up to Mari, or Ichirou, even. She’s just there, a deus ex machina to free Ichirou from prison or whatever else the situation might call for. The strangeness of her being a girl in a glass case, preserved and perfect and essentially a very horny doll for you, just makes her inclusion in the story feel prurient.

The book delves back into these themes of alienation within the time you find yourself, personal violation, cruelty and selfishness. Ichirou finds himself on death row, coated in a foul smelling spray which is impossible to wash off, so that in case he escapes prison, he’ll be identifiable as an escaped con by smell alone. That itself is one of the weirder sci-fi ideas I’ve heard, and I love it. Mari is returned to her awakened family, who decide Ichirou must be killed for what he’s done. She gets tangled up with a detective who has a pet pig and gets embarrassed every time he’s around a woman, making for some extremely uncomfortable “jokes” later on in the story when Mari lies bleeding out. Ichirou has a shoot out with some hired guns, a standoff with the detective, and a minister of state arrives to hire Ichirou.

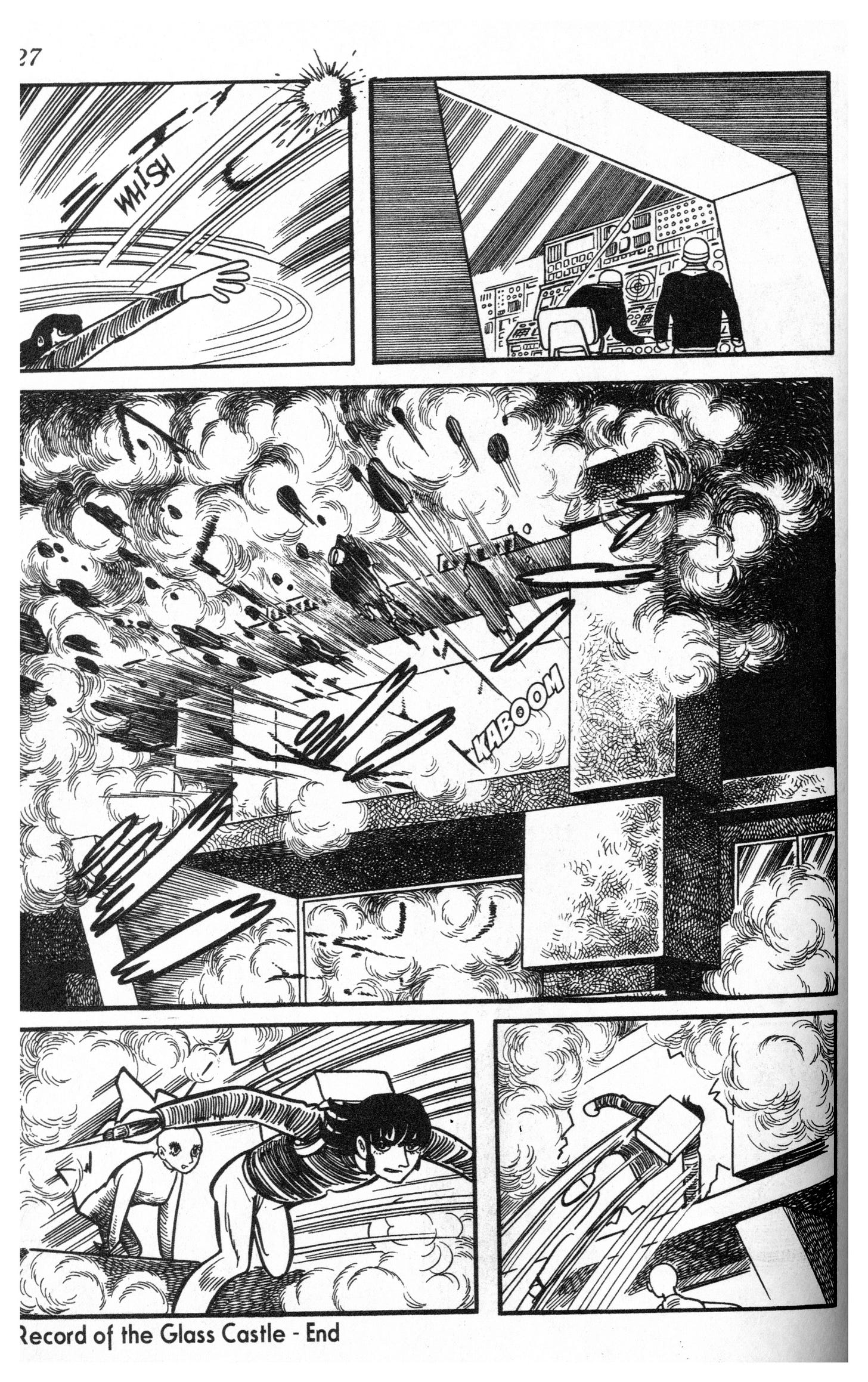

The minister charges Ichirou with killing everyone still in cryosleep in the REAL Glass Castle, a sudden change of stakes not twenty pages from the end and then…

I mean, that’s it. It’s so abrupt, so bereft of narrative foregrounding or sense that I assumed there must be a book two. There is not. This weird, violent, nasty little book ends on a strange transitional panel and that’s all she wrote. It feels SO incomplete. It is, for lack of a better term, random, seemingly made up on the fly by the end. So why do I like this book so much?

For one thing, I’ve always loved the lesser works of the masters. Save your New Gods, I want Etrigan the Demon. The stuff that didn’t catch like the bigger, more complete ideas are always appealing to me. I like to see incredible artistic ability thrown at bad and weird ideas. I like seeing any artist take a shot at saying one thing while saying another entirely by accident.

Tezuka had made adult work before. DORORO and THE BOOK OF HUMAN INSECTS do not share CASTLE’s bleakness or jaundiced view of the world. They do not feature protagonists as hateful as Ichirou. This is probably the book of Tezuka’s that comes at human nature with the greatest amount of contempt and venom. I don’t know if he personally possessed that view, and honestly, from the few interviews with him I’ve read, I doubt it. What the book does demonstrate without intending to is just as complicated and melancholy as anything Tezuka put there on purpose. It’s a book that I suspect was outside of his comfort zone and maybe even beyond his authorial range, and while it isn’t exactly successful in what it sets out to do, I really admire it for trying.

I’ve spent so much of this essay commenting on narrative choices Tezuka made, and I’ve hardly commented on the actual lines on the newsprint at all. This is because there is essentially nothing to criticize. Tezuka is not the god of manga because he holds the patent on speed lines, he’s a god of comics regardless of nationality because his artwork has almost the quality of a stamp. Perfect, seemingly machine-made, harder not to read than to read. This book features some of the strangest tezuka artwork I’ve ever seen, and some of my favorite.

Read CASTLE for yourself. Maybe you’ll be bored or frustrated with it too. I certainly was. I just couldn’t get it out of my head, and in returning to it, it opened up to me in a way I wasn’t expecting, that Tezuka may not have intended, imperfect and flawed, the multifaceted, complicated, weird, stupid piece of bullshit that it is.